The Sirkian Mirror

Douglas Sirk’s cinema work, initially disregarded, has been re-evaluated dozens of times over the years, with many considering his films to be run-of-the-mill melodrama and others claiming him to be a master auteur (Willemen). Sirk’s work seems to thread a line between sincerity and parody, mostly attributable to his studio obligations and his personal opposition to the scripts he was made to direct. Although restricted by contracts and studio requirements, Sirk was able to use the little bit of freedom he was afforded to create a lasting legacy. In 1955’s All That Heaven Allows, Douglas Sirk uses meticulous framing and staging of mirrors to add substance to otherwise customary scenes.

Douglas Sirk was notoriously bound by the studio system. Sirk became a house director at Universal Studios (Halliday 85), signing a seven year contract and being made to direct numerous scripts he didn’t find appealing. However, he was still allowed certain freedoms: “But at least I was allowed to work on the material—so that I restructured to some extent some of the rather impossible scripts of the films I had to direct. Of course, I had to go by the rules, avoid experiments, stick to family fare, have ‘happy endings,’ and so on. Universal didn’t interfere with either my camerawork or my cutting—which meant a lot to me” (Halliday 85-86). Sirk made up for the shortcomings of his studio situation by fully exercising his cinematographic prowess where he could. Mirrors and their psychoanalytical/metaphysical meaning have a long history in film studies, and Sirk utilizes them in his own way, as a way to signify relationships and drive narrative.

Fig. 1. Cary gazes at the branch from Ron. Fig. 2. Cary greets her children.

In All That Heaven Allows, mirrors are used to symbolize the subtextual relationships between characters and to progress the narrative. A mirror which Cary (Jane Wyman) uses to powder her face (see fig. 1) becomes the frame in which her children Kay (Gloria Talbott) and Ned (William Reynolds) are first seen. She gazes at the branch Ron (Rock Hudson) picked for her until her children (see fig. 2), as they will later in the film, come between her and Ron (the branch acting as a surrogate for him throughout the film). “In a beautifully composed shot, the children first appear reflected in the mirror, coming between Cary and the vase, and then, as the camera pulls away, she is taken back into the room and towards the children. This one shot tells the story of the dilemma that Cary will face for the rest of the film and is typical of Sirk’s emblematic, economical use of cinema” (Mulvey). The entire plot of the film is summarized in this one short shot–the first half of which, like Cary’s love affair with Ron, is unmediated–although we see her face through a mirror, her gaze is direct. Her connection with Ron, symbolized by the branch in the vase, is true. It is only when Kay and Ned arrive that our gaze, directed through the mirror by a dolly, becomes only that of a reflection. It is an imperfect, tainted image, not one of a real, true family, just the reflection of one. This family dynamic continues to be strained, and mirrors are frequently a part of this relationship.

Fig. 3. Cary stares off into space while playing piano.

The second time we see a mirror is directly in between Cary and Ron’s first kiss and the first time anyone from Cary’s life encounters Ron. Cary is seated and playing piano, but instead of sheet music of any kind, a long rectangular mirror sits on the music shelf (see fig. 3). The image is striking–not only in its beauty but in its impractical effectiveness. The film is full of illogical yet powerful mise-en-scène, such as the strange folding screen that separates Cary and Ned before he storms out on her following his dismissal of Ron. This piano scene in particular marks the end of the first act of the film. We have met all of the players, and the main conflict of the film is going to start building steam in the following scene. Cary is reflecting on her situation while being literally reflected through the mirror. A sort of identification occurs here, signified partially by the mirror–a common cue of self-identification in cinema–Cary, like the audience, is reflecting on the inciting incident, her first kiss with Ron. The next time we see Cary’s reflection is at the end of the second act, following Kay and Ned’s refusal to accept Cary and Ron’s relationship.

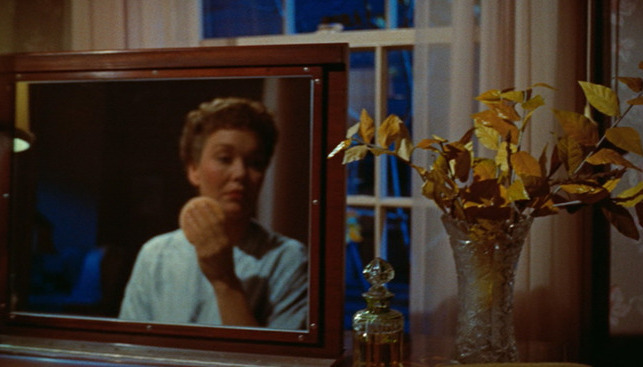

Fig. 4. Cary’s reflection in the television set.

Near the end of the film, after Kay and Ned have informed Cary that they intend to leave the home regardless of Cary’s sacrifice to leave Ron, they have one final gift before departing. Ned says a soft “Merry Christmas” before carrying a television set into the living room with a salesman. A reverse shot shows both Cary and Kay looking miserable on the couch before cutting back to what was described by film critic Fred Camper as “one of the most chilling moments in any film” (Camper). As the camera dollies into Cary’s reflection on the television screen (see fig. 4), the salesman says “All you have to do is turn that dial and you have all the company you want, right there on the screen. Drama, comedy, life’s parade at your fingertips” (Sirk). Cary is alone in the reflection while Kay, who is sitting right next to her on the couch, has her head obscured by a bright red bow in the corner of the television set. The shallowness of their familial bond is manifested through this gift; Kay and Ned believe their absence in the household can be filled by a television, their lives replaced by the hollow promise of company provided through images playing out on a screen (a screen she is reflected, alone, in).

Sirk’s mirrors are not only an aesthetic marvel, they are a part of the family, a part of the plot. What Mulvey calls Sirk’s “economical use of cinema” is on full display in All That Heaven Allows. Audience identification is ensured through the use of mirrors placed at specific points throughout the film, not only guiding us through the story but also allowing for deeper analysis than otherwise possible.

Works Cited

Camper, Fred. “The Films of Douglas Sirk.” Screen, vol. 12, no. 2, 1971, p. 54.

Halliday, Jon. “America II: 1950-1959.” Sirk on Sirk; Interviews with Jon Halliday, Viking Press, New York, NY, 1972, pp. 82–135.

Mulvey, Laura. All That Heaven Allows: An Articulate Screen, The Criterion Collection, New York, NY, 2001.

Sirk, Douglas, director. All That Heaven Allows. Universal Pictures Co., Inc., 1955.

Willemen, Paul. “Towards an Analysis of the Sirkian System.” Screen, vol. 13, no. 4, 1972, pp. 128–134., https://doi.org/10.1093/screen/13.4.128.